“That woman just came in here to take a selfie, then left!” I barely noticed, but the pair of 50-year-old brothers sitting next to me are besides themselves at her behavior. “What’s the point?” they ask.

I’m in Hubud, Bali’s hippest coworking space. A bamboo treehouse cum Internet café overlooking the rice fields in the center of Ubud; the place is Instagram-worthy, for sure. It attracts hundreds of pilgrims every month, people who want to wear the moniker of the hippest new trend: “digital nomad.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/1UffAVJsHB/?tagged=hubud

“Can you really be a digital nomad if you don’t Tweet and blog constantly about being a digital nomad?” I ask the man (the irony doesn’t escape me). He just looks back at me, quizzical. “It’s fucking stupid,” he says. He’s been writing code since before I was born.

The laptop in a hammock on the beach is a lie. Everyone knows this. The absurdity of this image is a running joke amongst the people who frequent Hubud. This idea is the face of the digital nomad lifestyle, and you’ll find it everywhere from blog banners to BBC stories to the cover of the digital nomad ur-text: Tim Ferris’ The 4-Hour Workweek. It’s a blatant lie, and it’s everywhere.

But that’s far from the biggest lie the Internet will tell you about the digital nomad lifestyle.

Digital Nomads are gentrifiers.

This is the crux of what we’re gonna talk about today. Nomads like to talk about their enlightened lifestyles, but when it boils right down to it, we’re just a new breed of hipster. We appropriate places and lead trends, we go where life is cheap but hip, and we are a little bit in love with our own lives.

None of these are bad things for an individual. But as a collective (and a rapidly-growing one, at that), we have the economic potential to destroy communities. I don’t see how anyone who has been living this lifestyle could see that statement, and disagree with it.

(But I welcome your counterarguments, after you’ve read the whole post)

Quick, what’s gentrification??

Good question! Gentrification is, essentially, an influx of wealthy people into a traditionally poor area. The wealthy people, who have much more disposable income than the area is used to seeing, pump that money into the local economy. Things are cheap: why wouldn’t you spend? Businesses boom, fortunes are made, and the once-poor locals are suddenly richer. Life is good.

AT FIRST.

The problem occurs here at scale, when a critical mass of wealthy people arrive. Your friend says “The cost and quality of living is really good here, you should come join me” (sound familiar?). And eventually, you do. So do two of your friends. Each of them brings two more friends. And so on. Soon, rich white people are everywhere.

Upscale restaurants start opening to cater to this new class of customer; rents start going up; more people start moving to the newly hip area. The cycle accelerates. More and more money enters the equation, and soon the people who originally lived there can’t afford the property taxes on their own homes.

This is exactly what has happened in the U.S. cities of New York and San Francisco. Trust-fund hipsters did it to Brooklyn. Tech startups priced the soul out of San Francisco. Wealthy Chinese investors are fueling the phenomenon in Vancouver, Canada. Gentrification is even beginning to happen in my home state of Colorado, where legal weed, a booming tech scene, and an outdoors lifestyle are bringing hundreds of thousands of the nouveau riche to Denver. As a Colorado native, I hate it.

Yet, here I am, halfway across the world, part of a group that is driving the exact same thing in the remote work hotspots of Chiang Mai, Thailand, and Ubud, Bali.

We are not a force for good in these communities.

As I said, I’m writing to you from Indonesia. Ubud is Digital Nomad hotspot number 2, probably, behind only Chiang Mai, Thailand. Ubud is a great town. It oozes creativity, charm and spirituality. I love it. I’m hoping to be here for the next few months of my life, eating Instagram-worthy meals, developing my meditation practice, and resetting my chi.

(God, even I hate myself.)

Ubud is cheap, too. Good food, healthy food, and a quality lifestyle come without too much effort, provided you have US Dollars to spend. Which I do, and you likely do too.

Which brings us to a second term:

Currency Arbitrage

Currency Arbitrage technically refers to trading currencies between different brokers at different rates in order to profit from the act of exchanging money from one currency to another. For this case, we just need that last part:

Currency arbitrage, for a digital nomad, means earning wages in one currency while spending in another, weaker currency.

One USD equals 35 Thai Baht. Right now, 1 USD is equivalent to 14,000 Indonesian Rupiah. And those rates have been going up steadily since I arrived in Southeast Asia. This means that I have been getting small pay raises almost every single day since I arrived in Asia, even though my salary, in terms of USD, has remained completely unchanged.

That’s arbitrage.

Pictured: about $60

Currency arbitrage is what makes the digital nomad lifestyle possible. After all, most people who identify as remote workers, location-independent entrepreneurs, drop-shippers, or whatever bullshit they’re trying to do, simply couldn’t afford to do those things in the U.S. (developers excepted). They definitely couldn’t afford to do those things while traveling around an expensive Western country, where their currency only goes so far as a covering a middling apartment, drinks out once a week, and maybe a car payment.

That currency goes soooo much further in a foreign country. It’s absurd; and, when it’s a fact of your day-to-day life, there’s no denying that it’s awesome. I eat out every meal; I drink fancy coffees; I buy taxis; and I take overpriced tourist trips. And I usually have money to put into savings at the end of the month.

This is why people come to Southeast Asia. People will tell you it’s for other reasons, like the culture or the food, but this is reason number one. (Chiang Mai, especially, is rotten in this regard. Thanks, Internet.)

Selling the nomad life is an industry unto itself. And not a great one.

To eat healthy, raw, vegan meals three times a day with wheatgrass shots and pure cane sugar will quickly bankrupt you in any major metropolitan area. You know the restaurants: you see them on Instagram, then you check the menu and wonder how your friends can even afford to eat there.

You can eat at those places in Bali. A table-filling meal for two, including fancy drinks, wheatgrass, smoothies, probiotics, dessert, and whatever else you want will almost never run you more than 280,000 IDR, or $10 per person. And the food is just as good and just as pretty as it is in Brooklyn or Austin or Portland. And it’s probably healthier, to be honest.

Put against a domestic context, I feel like I’m winning at life when I eat a meal like that, and walk away having paid less than the price of a Chipotle burrito (no guac).

And on a micro level, I am winning. In that tiny moment, I did good. I helped a local business, I put money into the island’s economy. I’m improving myself, I’m getting healthy, and I can nurse a small, secret sense of superiority over my friends back home. All good, right?

Not quite.

We’ve looked at the microeconomics of my hipster lunch. But what are the macroeconomics of such tourism??

This is where things start to fall apart.

Let’s talk about globalization.

“Economic globalization refers to the increasing interdependence of world economies as a result of the growing scale of cross-border trade of commodities and services, flow of international capital and wide and rapid spread of technologies.”

—United Nations

Is globalization a good thing, or a bad thing?

This is a big question. We could debate it for years without ever finding a definitive answer. But, from my point of view, in this context, globalization is a very bad thing. A thing whose effects will only compound as more and more people are attracted to the digital nomad lifestyle.

Globalization has huge, far-reaching consequences which aren’t always immediately apparent.

Consider the humble Thai taxi driver. These guys are ubiquitous: as a tourist in Chiang Mai or Bangkok, you can hardly walk down the street without being asked seven times if you need a tuk-tuk. Why? Because westerners are happy to pay higher prices— it still seems “cheap” to them.

But here’s the thing: your fare isn’t cheap, it’s expensive. It seems “cheap” because we have such a different standard of wealth in our home country that forking over 230 baht or whatever for a taxi ride seems great. Even more convenient than Uber, and the driver’s about as intelligible, you think. He gets you there quickly, defies traffic laws seven ways to Sunday in the process, chain-smoking all the while. You give him 250, tell him to keep the change, and go on your merry way. You’ve spent $7.

But if that happens enough, taxi drivers stop picking up Thai people. They only look for tourists— there is more money to be made. The local Thais, who make in a day what I make in an hour, cannot afford to see things the way I do. My “cheap” is their “expensive.” And my desire for cheap things is driving up their prices and their access to vital services.

Yes, the taxi driver personally benefits when I pay him a high fare and a tip on top. His family eats well that night. But after a year, when my digital nomad friends and I have been spending our money all around town, everything is a little pricier. Every year, he is able to afford a little less. Every year, provided my currency remains strong, I am able to afford a little more.

And while I can leave, he’ll always remain a taxi driver. I can enter his world, wield my economic influence, and then leave without seeing the consequences.

This is gentrification at its simplest. This is globalization. This is the result of some very selfish, very narrow thinking.

Every dollar we spend, every blog post we write, and every coworking space we patronize contributes to this inequality.

Digital nomads are unintentional pawns in a new wave of economic imperialism.

Tourism has existed since before you could get on an airplane, of course. Currency arbitrage just as long: one imagines Columbus arriving in the New World, tweeting back to his buddies Spain: “Holy shit I just bought 4 islands for one silver coin #ballin #GetTheFuckOverHereBros”

(Columbus was basically the Martin Shkreli of his day.)

The digital nomad, of course, is not Christopher Columbus. We don’t come with any ill intentions. We come, usually, with an earnest desire to see the world and learn more about other cultures and customs. We are not intentional homewreckers. And maybe that makes a difference. I don’t know, yet. But we are destroyers just the same.

This lifestyle, as sweet as it is, is built off the back of impoverished nations, and the exploitation of less privileged people.

I’ve been here for three months, and the plan is to be abroad for a while longer. These are thoughts that never occurred to me while planning this year of my life. And I read a LOT of digital nomad blogs. It is true what they say, that travel opens your mind. So here I am in Indonesia, wondering if I belong. Travel has taken the top of my head off, and suddenly things don’t seem so simple.

Maybe I’ll hop over to Europe, see what the scene is like in a more developed zone. I have a lot more learning to do, and I still want to see the world. I am sucking the marrow out of life and enjoying every moment of my travels. But living the “digital nomad” life over here in Asia just doesn’t feel ethical, right now.

There are big consequences to these trends, and no one seems to be talking about them.

So let’s talk.

Postscript: I’m sure there will be some people who are very offended by this piece. It’s not the easy, breezy stuff you usually see written about this space. Which, in my mind, makes it all the more important to talk about.

This piece is rough around the edges, and I’m sure my ideas could use some refinement. I know my perspective will continue to evolve after another three months on the road, but I had to get this off my chest now.

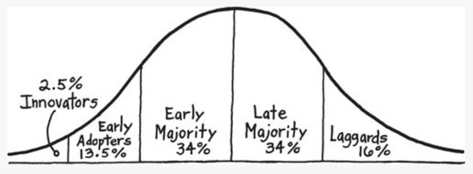

There’s a definite sense of cutting-edge in this community: it’s truly global, full of men and women from every place imaginable. We think outside the box, and hustle for ourselves. We create our own value. But we are in the “early Adopter” section of the curve. While the “innovators” will kick and scream they’ve been doing this since ’98, true scale is yet to come to the community. It will. And when it does, it will be too late to answer these questions in any significant way. The damage will be done.

So, to those of you who are also on the road, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Help me have a dialogue about this issue. Please! Comments are open. Blog up a response. Tweet me @thatisyouth. Or let’s chat over the watercooler at Hubud. I’m here for another month.

Then, who knows?

Ciao.

I think the biggest perspective for the digital nomad is to make some sufficient efforts to be a part of the local community. For ex : learn the language and do not stick to english (or french or whatever) Then stay a little while and see how it is going on for you.

It is the same everywhere. People with more money are everywhere. It is not just tourists on locals. It is simply who has more money has more choices. Nothing new. Ciao!

I agree wholeheartedly!

Hey liked your post, and I totally agree with you, Digital Nomads do hurt the economies of local cities but I also think we are basically just like extended tourists so we do the same damage as any other tourists. I live in Barcelona and have been Europe (france, italy, norway, london, spain) for almost 14 months now as a digital nomad. Just being in Barcelona I hear locals tell me about what it was like in 2012 and before. In just 4 years the entire city has changed because of the tourism they tell me, people bustling everywhere, thousands of illegal AirBnB’s, people can’t afford rent, people can’t sleep because of the partying. But also people are doing great because of the tourism as well. I have been here for the summer of ’16 and this summer and even since last summer I saw restaurants and stores up their prices by 20%. People from all over Europe flock here to open up businesses of all kinds, tiny little gentrified restaurants that target and suck money our of tourists. 5 Start restaurants here are now more expensive than restaurants in Houston where I am from, paying about 50 – 100 euros per course meal. So I see the effects in first hand of tourism.

On top of that digital nomads with USD living in the EU do not enjoy Current Arbitrage, at least not in tourism stricken cities like Barcelona, it’s quite the opposite for me paying almost 1.20 on the euro right now. So everything is not cheaper for me living here, in fact its about 10-15% more expensive living here than if I lived in the US.

For those lucky enough to be able to travel, it truly expands the mind. When you look to see the things many people worry about and fret over here in the USA, they are decidedly first world problems. People too often have that first world perspective, which colors how we perceive other cultures. No simple answers and many questions. Well written and provides a mature insight.

Reblogged this on 10,000 Miles & More and commented:

One of the most thought-provoking pieces on travel I have read in quite a while. it deserves a (far) wider audience.

This post is eye opening and excellent, though I don’t consider myself a digital nomad yet.ni know I am somewhat active in the community. Sometimes we definitely need to consider the impact of our presence and how we are perceived.

Thank you for having the courage to post it!

Incredible article, superbly written! It’s deeply informative and sheds light on something all too invisible. Thanks so much for checking out my blog as well, it means the world!

http://Www.apocalystblog.wordpress.com

Kudos! A brilliant post that without question spurs a thousand more conversations. As I was reading these, a lot of questions were whirring through my head, and I was wondering whether I could pick your brain on these:

– If you take a bit of a step back, “wealthy-earner-pumping-money-to-a-destination-where-he-temporarily-resides” could also apply to any tourist, whether he’s a digital nomad or not. Is there any location where tourism is not harmful? What can we learn from these locations? Why is tourism okay for some locations, and not for others?

– Is there actually any way that remote workers could be ethical temporary residents?

– Could it actually be a bit patronizing to think that once foreigners pump money into an economy, the locals will turn on each other, as in the “taxi driver” example? Could it be actually possible that with the extra wealth locals suddenly have, they take the opportunity to build long-overdue facilities for their own community? O maybe this is just my chronic optimism in overdrive again.

– On the flip side, once people capitalize on suddenly “hip” locations, what happens to the traditionally “prime” locations? Do prices then drop as demand decreases, making the area more affordable for people, if the so-called “invisible hand” steps in?

It’s a madman’s dream of mine to become location independent. Cities like Zagreb in summer are appealing because of the cost of living, my need for travel, and my (*cough*) bank account. But being a Brooklyn Boy, I’m no stranger to gentrification and saw how it transformed two neighborhoods I couldn’t afford a latte in now. But in a lot of places I traveled to I couldn’t. And in a lot I could. How much “easier” am I really making my life if I’m negatively impacting somebody else’s? Choose your location wisely. I may need to be as unhip as possible. I may need to redefine what working remotely means for me. Hotspots like Thailand and Bali never seemed like a good fit, never gave off a sense of a place I’d belong in. Your post validates a lot for me. Thanks, brah.

i agree with the sentiment of all that you’ve said. as a frequent traveler and a native New Yorker, similar observations and conclusions have crossed my mind. after much thought i believe that *as an individual* it is my responsibility to be as mindful with my spending and behavior while abroad as possible. however, the responsibility for curbing the potentially negative effects of wealthy travelers like us (relatively, all Americans who earn in dollars are wealthy) rests with the central planners, that is, the government, of these countries. we do have responsibility to be mindful since several individual actions adds up to a cumulative effect, but we are not even capable of keeping the best interests of others’ in mind because we are foreigners. to think otherwise is rather paternalistic (and oh so American 🙂 – said by an American ).

Right on

AMAZING!!

Fascinating article. Well written and lots to digest. I am not in the DN phase of my life but perhaps when I am more free to travel I’ll think back to these points and behave appropriately.

Thanks for stopping by my blog, too!

Brilliant! You have captured so much of our zeitgeist. Even the refusenik succumbs to the malaise of self obsession.

This article is terrific, amazingly insightful and spot on. The same thing happened in the N.Y. Hamptons on a mega-wealth scale. The only difference in modern globalization; and what happened to the American Indians, for example, is that neo-hipster intrusions have not killed the indigenous populations with diseases such as Smallpox. Which, of course, could have really accelerated the process geometriclly

Great things to think about – thanks!

Whatever the cost it seems you’ve found a way to make it affordable. You’ve captured an interesting lifestyle.

I lived a similar lifestyle 40+ years ago when on active duty. Stationed in Thailand, when the Baht was 20 to the dollar, my meager military salary as a low-ranking enlisted made me rich in comparison to the locals. I still have fond memories of my times there and the people I knew but I am settled now and would not change.

Enjoyed your post, despite the self-recriminations. 😉 Seems to me that “gentrification” is little more than a newish word for something that’s been going on ever since our distant ancestors left their caves and experimented with above ground living. It’s part of the human experience, much like many other negative side effects of civilization. I suppose it’s noble to consider one’s location on the hampster wheel of “progress,” but unless one generates an outsize impact, feeling guilty about it doesn’t accomplish much. Perhaps some generosity toward the needs of the impacted locals would do more good. What the hell, you’re already there. What could it hurt? Just a thought.

I still haven’t embarked on my own grand adventure yet, but I’m so happy to see some honesty out there surrounding what “digital nomadism” really is and the impact that it has on locals. The idyllic pictures that other bloggers paint really ignore some of the problems at hand. Well done!

The problem is a lot of those other bloggers make their living by selling their lifestyle to other people. Which-while good for them-is often not great for the people on the receiving end!

Not on the road myself, but this was a great piece, Daniel. Lots of food for thought. Many thanks also for your like of my Norman Maclean blog on A River Runs Through it.

I’ve travelled for decades, well before digital arose! You make some totally valid points clearer than I was able to express at the time I was an expat in India … fortunately I still have contact with one lady who didn’t get my points that paying excess taxi fares, etc was spoiling things so have passed a link to this article on. Thanks, keep thinking and digging deep, means a heap.

Wow, thanks for vocalizing this issue. To be honest, I’ve always been sort of averse to this notion of “wanderlust” that is so divorced from the economic impacts it has, as well as the (typically) white privilege that it is predicated upon. I think keeping an open dialogue about the choices we make is crucial, and I like how you’ve opened the door in a way that doesn’t appear overly-adversarial, which I think can be the toughest part. Thanks a lot, I will definitely be keeping up with your work. Take care.

I love to travel and work for myself, but I definitely don’t fit into the category of hipster. As someone who is a big fan of traveling and working from my laptop, I agree with most of your points.

I visited Brooklyn and had friends who lived there when it was still cheap and seedy. I’ve also seen plenty of social media whores during my travels and at home who seem to care more about how their lives look to complete strangers on the internet than actually living and enjoying it.

Once a location is “found out” it usually ruins it for me. Being a surfer, my travel itinerary usually includes a quaint place with warm water surf. I’m all for making the lives of locals better by bringing in more money, but sometimes I am embarrassed by the behavior of other travelers.

Gentrifiers–that’s what you called it. I hear that.

I often wonder what are they tethered to?

Why the tether?

Digital imperialism.

Turning the real world into a flat screen tv television program–of course you need a selfie!

Otherwise you have no credibility. 🙂

Keep it small until it gets too big, then get rid of the sh*t.

Easy peasy.

Thanks for the inspiration!

Tethered???

Awesome piece.

This is part of the reason why as a traveler, its important to be very attentive to local customs.

While its fun to pull the “damn straight I’m American!” at a bar, it can be dangerous to throw around “cheap” currency as if it was the loose change we see it as.

Spending like a tourist is just as bad as acting like a tourist. You become a target, you stand out, and you contribute to the tourist-ification (I’m sure there’s a term for this) of the community and its industry.

Awesome article man

Very thoughtful, interesting piece. Thank you for this perspective.

With all due respect, not everything revolves around digital nomads. In fact, I think that you are overinflating the digital nomad’s footprint.

Sure, they bring in currency arbitrage but it’s only a drop in the ocean when you consider locals that become ‘foreigners’. They are those born in that country (ie Thailand), they then immigrate to a wealthier country, and upon visitation bring in their new country’s expectations in terms of the cost of goods and services.

Take for example the Philippines and balikbayans. They could be born in the Philippines, later immigrated to a wealthier country but they would bring in cash back to their families in the Philippines. They could be buying property there, thus contributing to the rise in property. They are one of the main reasons why the Philippines have luxury hotels and malls bordering on to slums. The same goes with other countries that have had locals that immigrated to wealthier nations only to come back and exert their economic influence on what was previously their home country. I consider myself a digital nomad, but I’m also aware of the balikbayan influence on the Philippines. This isn’t something that you’d know though 😉

Yes, that’s a valid complaint I saw in the Reddit thread 😉. I didn’t mean to imply that nomads are entirely or even majorly responsible for these issues—we are obviously a relatively small economic segment in a vast system of inter-connected forces.

But as I cannot think about the way the entire world is connected, I have to look at only my own small communities.

Do you have a recommended piece of reading about balikbayans? I would love to learn more.

Another sad reality that I have seen happen before my very eyes also has to do with currency arbitrage, only in a much sleeker form.

A farming village out in the middle of nowhere slowly steams along their merry way. Telecoms are a rarity with mobile reception only on some high peaks. Maybe some humanitarian doctor equipped with a satellite phones lives there. Now a company like XYZ-Mining comes along and discovers a valuable mineral. Everybody rejoices as it creates jobs in the village where before, no one had “jobs”. Normally they had to swap each other for commodities.

Unfortunately, they mine only employs 20 of the 40 young men living there, totally overlooking the women and older men. So these guys earn major dollars.

So instead of swapping chichen for bread, the farmer now wants dollars. This also start to skewer things and result in a different kind of gentrification.

Sad but true

It sounds like your saying digital nomads are a cause of gentrification and globalization. Does that make every tourist equally guilty? What if you work remote but you don’t travel, but stay in your own community? What if you actually don’t make a ton of money as a digital nomad and aren’t going out to spend it at coffee shops all the time?

It sounds like your saying digital nomads are a cause (or at least a large contributor) to globalization and gentrification. I don’t really buy that. Gentrification and globalization are caused by underlying economic practices, mostly pushed by large corporations, that in turn determine how and where money is spent. Do you have any data to support your hypothesis that digital nomaders are the ones making this impact?

If anything, being a digital nomad allows me freedom that separates me from large corporations, I can then move around my town and address the technical needs in my community rather than working for a giant that is going to use the profits I earn them to buy legislators. I know this is just my anecdote, but most evidence in this article is also anecdotal. Don’t assume every digital nomad is spending money the same way you do, hipster.

Just some food for thought, my man. I admire your passion though.

You’re right, the arguments in here are certainly applicable to regular tourism as well, in some ways.

Certainly, being a nomad allows you immense freedom and economic mobility. This is the appeal of the lifestyle.

But when you enter an impoverished community as a high-earner and little intent or understanding of the place you’re visiting, you exert a powerful influence you may not feel. You mention ‘my town’ and ‘my community’ a lot—which is exactly my point.

Most nomads don’t have a ‘my community.’ They are passer-by in many communities, and often unaware of the effects their cumulative passing has.

But as I said, I welcome the discussion. It can only do good to talk about these issues. You should write a counter-argument post, and I will link to it here. 🙂

So, few follow up questions. In discussing gentrification you point out that “…soon the people who originally lived there can’t afford the property taxes on their own homes.” Why is that precisely?

You seem to be implying that New York, San Francisco and Vancouver are now worse off than they were at some point in the past. In what ways are they worse off specifically?

In discussing your Taxi driver friend you point out that “But after a year, when my digital nomad friends and I have been spending our money all around town, everything is a little pricier. Every year, he is able to afford a little less. Every year, provided my currency remains strong, I am able to afford a little more.” Why are you making the assumption that everything except cab rides will get more expensive?

“This lifestyle, as sweet as it is, is built off the back of impoverished nations, and the exploitation of less privileged people.” Examples of exploitation?

Many good questions here about big topics!

Instead of writing a loooooong comment, I think it’s best I take some time, do some thinking and some writing, and put together a follow-up post.

I am in Budapest currently, as I hinted at the bottom of this post, and my understanding of the issue certainly continues to evolve.

Look for it hopefully in the next couple of days!

Just a quick note, they didn’t assume that taxi prices will remain static.

“But if that happens enough, taxi drivers stop picking up Thai people”

So that happens. They also note that the price of _everything_ will go up, and that will likely affect the taxi driver negatively long term more than the short term positive boost. They even noted that other Thais who aren’t getting cash from tourists don’t even have the short term positive boost, it’s just downhill city for them.

And if you want to know how those cities are worse off then I suggest looking at housing prices, at the amount of locals who can’t afford a house, and at how the cities are sprawling as people who used to live relatively near their work are now being forced further and further out. This means their savings are being redirected towards increased commute costs and they become working poor.

This is in no way a good thing as it accelerates the end game of capitalism, which is blatant feudalism as people start to become unable to afford to work, let alone pay for healthcare and the like. Outside money very rarely helps locals unless it’s heavily controlled, e.g. Norway’s oil money.

Even though I don’t agree with all your points you’ve brought a lot of great issues (and some new ones) to shed some light. Thanks for a sharing this great post.

Really insightful post. I harbored this fear for a while during my travels but you’ve articulated so well what I could not. I’m also not sure what the answer is – hopefully beginning to talk about it and opening up the difficult conversation is the first step.

Thank you! It’s great to hear the point of view from an actual digital nomad, rather than an article from “Forbes.” I write on language-learning, and I’ve found that the language-learning and digital nomad crowd converge a lot. I wrote about the ethics of this lifestyle, too, at https://lovinglanguage.wordpress.com/2016/09/26/language-hacking-%e2%89%a0-language-love/, if you care to take a look.

I loved this post so much I just had to share it. When I lived in China and taught English I ended up questioning a lot of things. It quickly became apparent that my western features more than my teaching skills were what I was being paid for.

Thank you for this incredible post! I’ve been thinking about globalization and tourism and how to travel ethically. Like you said, dumping money into a poorer economy works well for those with American dollars, and on the short term, for the community. But in the long run it always drives up prices and cuts away resources for local folks.

It’s a lot to think about. I try to consume “ethically” (as much as I think that whole idea is/might be a farce) and hopefully I can travel without spreading imperialistic, capitalistic prices that deny others.

Really great article. I thought about this a lot when I was younger. A lot of my friends were going on missions trips, and I always wonder what the local people thought of a bunch of rowdy teenagers rolling in for a couple of weeks to do something for them.

Versus with them. Or at their request. Maybe they were super grateful. Maybe they changed lives. Maybe they didn’t.

My daughter is 16 and entering grade 12. I am about to enter a new era of unprecedented freedom. And I think that before I start traveling, I am going to have to think about how I am traveling. So I can be more than just a person collecting experiences when those experiences are people’s lives.

This is an important point. One problem I see is that people invest a few weeks or months of their lives in a community and move on. People don’t invest their lives in a community. The fact that we don’t know what the effects were 10, 20, 30 years after our trip is telling.

Thank you so much for highlighting this issue. I met a very pleasant American lady in Nepal and we discussed about the issue of native English speakers being much more preferred by locals than local English teachers. Native English speakers earn much more too so they can afford to live very comfortably. I can feel that she is such a decent human-being for raising such concerns while contemplating about the moral consequences of her future direction.

Fascinating story. I hadn’t thought of that, competing for the same jobs locally.

Awesome piece! I appreciate you sharing. I am wrapping up my last year of college and have been investigating the digital nomad lifestyle. I hope this message finds you well!

Thanks Shonnan!

Hi! I’ve just found your post: months later, are you still a digital nomad? What do you think about the ethics behind this lifestyle?

Good question! I am still working remotely, although I’ve returned home to recharge for a bit and think about my next move— travel is tiring and being a DN can be extremely lonely! I think I will write another post addressing this question in more depth, but here’s a few off-the-cuff thoughts:

*I still believe digital nomadism is a selfish and exploitative lifestyle.

*HOWEVER, it is understandably highly appealing. The ability to pursue career goals and personal travel goals simultaneously is an opportunity it’s hard to say no to.

*The competition to live this lifestyle is going to fiercely increase in the next decade, meaning if you have the opportunity to do it now, this is the time.

*The macroeconomic forces unleashed by DNs are harmful to the communities they visit. Of this, I have no doubt. Nomads will often say the locals are glad of their business— and they will usually tell you they are— but this is deceptive because many of the people in these places aren’t educated enough to understand or fully grasp the impact of these big trends.

*Taipei, a big developed city, is where I felt the least exploitative.

*Nepal, a place most DNs avoid because of the poor Internet, is where I felt my dollars were most LEGITIMATELY needed.

*The DN hotspots of Thailand and Bali were where I felt the most uncomfortable about the lifestyle— perhaps because it is so visible there.

So as I type these out, I have to say that I still find the lifestyle unethical. Whether you can justify it to yourself is a matter of personal beliefs: there’s certainly a case to be made that economic globalization and outsourcing has reduced the quality of life attainable for ordinary people in the developed world— going nomad could be one way to reclaim that higher quality of life.

But, and this is a fact most DN bloggers gloss over, such an improvement not without its costs to the communities you visit.

Excellent post, bro. You bring up a lot of good points. My thought is, you don’t have to be that person who is a harmful influence on the area. Learn about the place where you are and spend mindfully. You can still have the fancy dinners at restaurants geared for foreigners while not overpaying your taxi driver. Just because you have enough money to pay exorbitant prices doesn’t mean you should. If you spend some time hanging out with real local people and just observe, you will probably learn a lot about how to live in a place without being a destructive force. I still think that pumping money into a low-resource economy by buying goods and services is generally beneficial. It helps people grow their businesses and progress out of poverty in a dignified and sustainable way. If they sell more, they can buy more inventory and in turn sell more. There will always be customers to purchase their goods and as long as you are a mindful consumer who doesn’t contribute to unrealistic inflation of prices, it won’t matter whether the customer is local or foreign. Another part of globalization that is more harmful in my view and you did not touch on here is that it puts economies of very different scales in the same market. So the American corporation who is producing corn on thousands of acres of land with machinery is marketing to the the same buyers as collective of African farmers who are doing everything by hand and cannot match the prices of the huge corporation. So the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. But that’s a topic for another blog post. Very thoughtful post! Good to see you tackling the tough questions.

“economies of very different scales in the same market” is well-phrased. This sentiment sits at the heart of the post, I think.

Globalisation, gentrification and currency exchange are all heliishly complicated topics which we could spend many moons talking on.

I’m sure I’ll be taking a few more swings in the next few months.