Since this is the Internet, you get the crude title, and the summary up top.

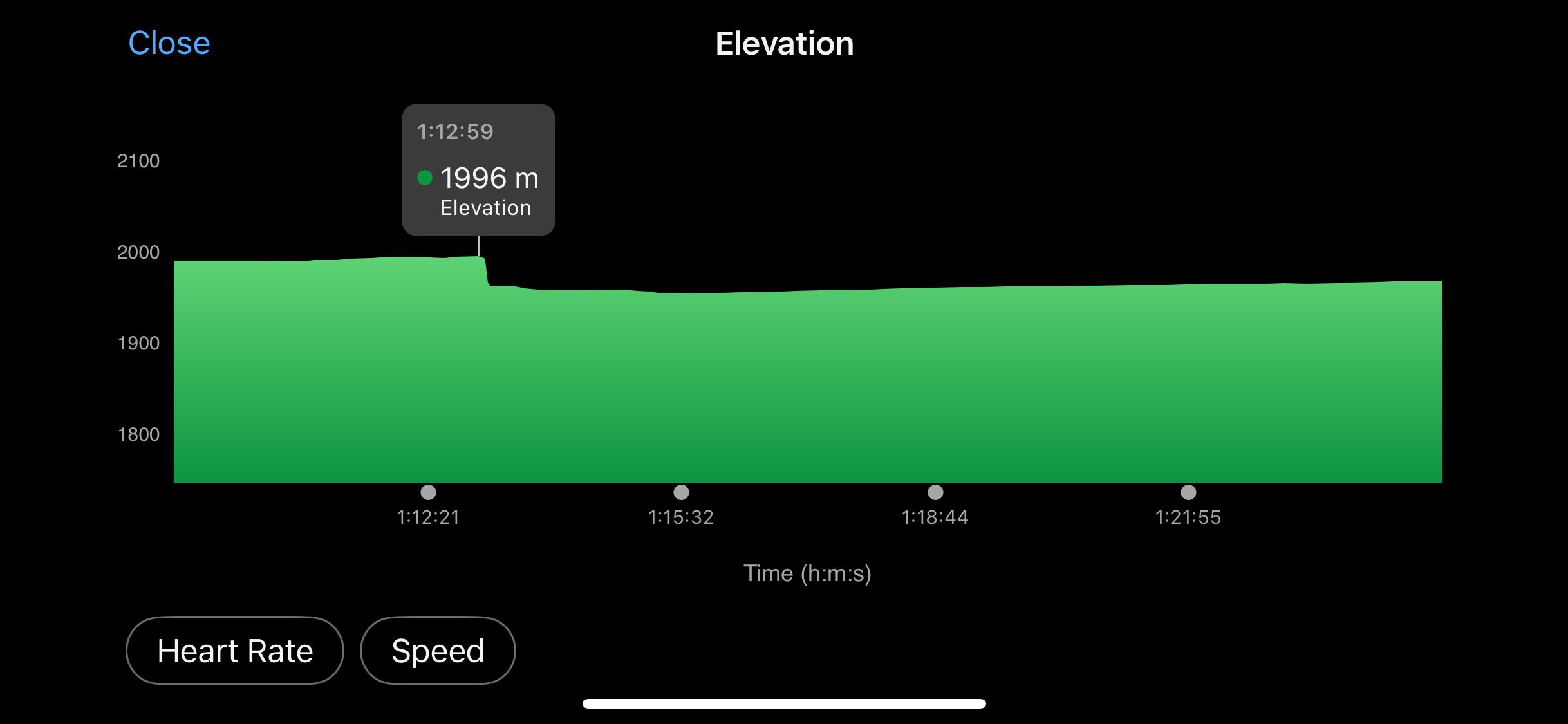

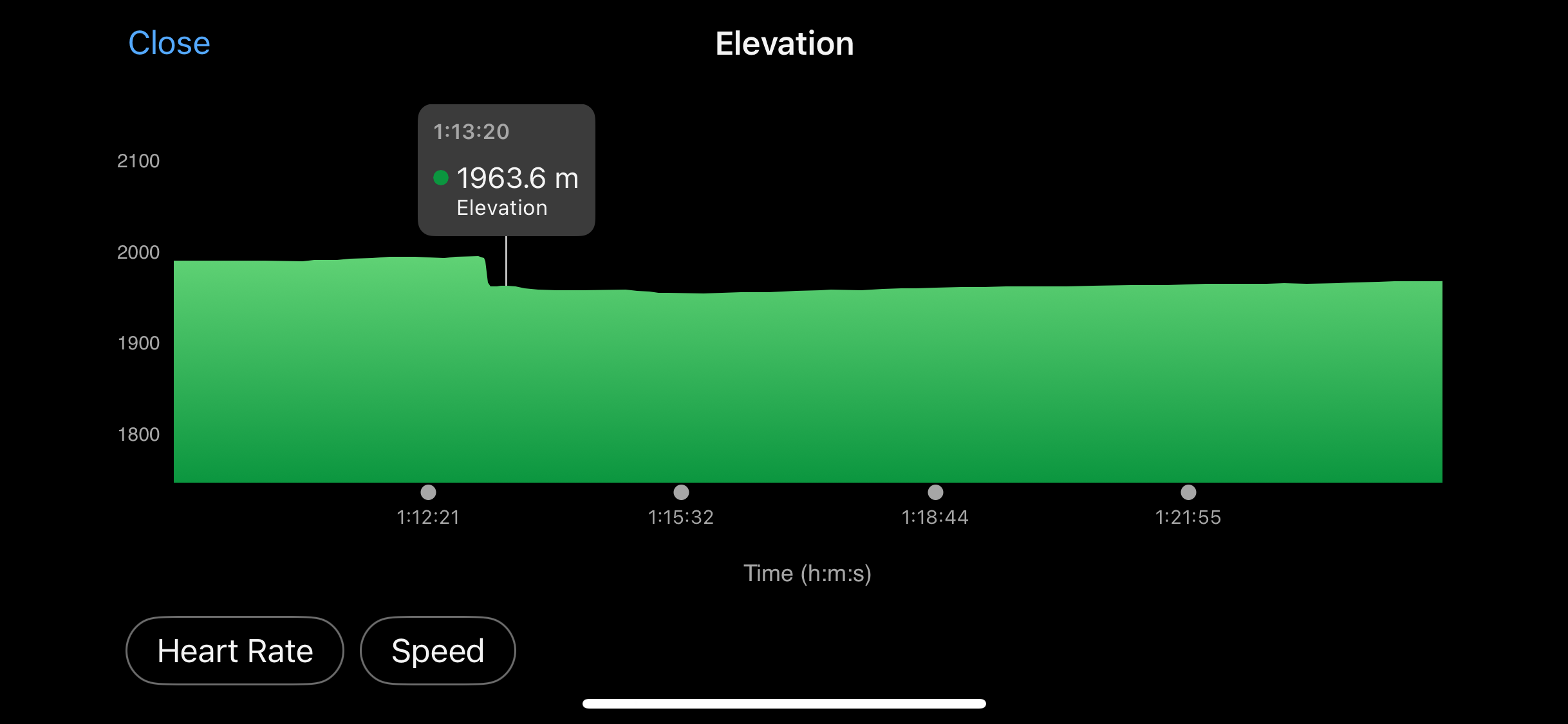

The short version: yes, I did fall ±100 feet trad climbing in Eldorado Canyon (My Garmin Fenix GPS watch measured a drop of 33 meters – 108 feet). I was runout on easy ground, lost balance, popped a piece, fell way past the next one, and was caught on a Gri-Gri. I broke my left foot in two places (fifth metatarsal, non-displaced calcaneus fracture) and had two cuts to the face which required stitches (5 in the left eyebrow, 11 in the forehead/scalp). No surgery for the foot. The incident easily could have killed me, but instead left me with a relatively minor 10-week recovery.

The long version, after the jump.

(Warning: there will be a couple bloody pictures)

A few weeks later, besides the occasional throbbing, the heel feels fine. The metatarsal, in the same aircast, is inoffensive — inconvenient at worst. The scary cuts on my face have healed: the eyebrow so expertly stitched that you’d never know; and the other scar, the angry red line from my forehead into my scalp, hides perfectly under my mop of curly, oft-complimented hair. You could not ask for a better outcome.

It’s easy to imagine: someone catching a glimpse, touching my face, brushing the hair away. Looking closely, narrowed eyes. Tracing the scar up into the scalp, the spot where they closed my skin with staples, and asking: how’d that happen?

The imagined scene is silly, I know. The answer is simple.

“I fell.”

It was a route I had climbed before. I was done with all the difficulties. I even had both feet on a ledge. As I had done on a hundred other climbs and a hundred other days, where boldness was required and I rose to the challenge, I had absolute confidence that I would not fall. And yet…

That feeling of loss of balance—everyone knows it. A rolled ankle in a basketball match, a missed step in the dark. That roller-coaster-drop in the gut. And if you’re lucky, waking from the dream with a jolt, safe in your own bed.

As I experienced that familiar vertiginous feeling, many meters above the last anchor attaching my rope to the wall, I had only time for one thought:

This is gonna be bad.

The angle of the climbing had made it easy – too easy to require protection. I had placed only one cam in this section, and even then, only to direct the rope for my second. Jammed in a shallow pocket of rotten rock, I knew it would not catch a fall. Confident in my ability, I had not worried, not a bit, up until the moment I toppled backwards.

The slabby angle of the cliff meant contact with the rock was unavoidable. The thin rock climbing shoes provided no cushion as I hit my heels, hard, on the less-than-vertical rock below. My perspective became tilted, blurry, and unrecognizable.

As I clothes-dryer-spun down the rock, I sensed the cam pop. A slight tension came into the rope, and then a release, as the spring-loaded device turned the energy of my fall into outwards pressure strong enough to explode the fragile rock in which I had set it.

These understandings would come after. The real-time experience was rapid, violent, and random.

My next piece of protection was far away, a nut on a double-length sling in the apex of the crux roof. I bounced again, off the wall, inverted, and started to fall freely as I passed the overhang. My belayer says this is where he first saw me, upside-down and headed down — fast. I saw the ground as I accelerated. Maybe this is it, I thought. And as quickly as it had started, the rope pulled taut, my body flipped upright, and the fall was over. I didn’t even have time to scream.

I looked down at my belayer in shock; we were quite close together now. I had been approaching the anchor, a distance I knew to be almost a full 60 meters from the ground, before I fell.

Blood dripped rapidly from above my eyes, staining my hands and my pants. “Down,” was all I could say, pointing at the ground. “Down, down, down.”

“I don’t think you did anything wrong,” my friend Calum opines, after hearing the story.

It is the first week of my recovery. I am uncomfortable on the crutches, and my feet hurt at night. My forehead and eyebrow are still held together with itchy stitches, and the urge to pick at them is becoming intense.

“We work to be able to climb quickly through easy ground, to place less protection where it’s not needed,” he says. “It sounds like that’s what you were doing.”

My friends have gathered for a game night; a show of support since we almost never undertake activities which are not climbing or related to climbing.

“Mate,” I say with a forced laugh. “My foot wouldn’t be in this boot if I hadn’t done anything wrong.”

Calum argues on, defending myself, to myself.

I feel the love. But more than anything, I feel embarrassed.

At the Emergency Room, we are seen immediately.

This is never a good sign.

My belayer and I have estimated the fall at sixty feet, a figure the receptionist repeatedly tries to confirm as “six.” We correct her, politely but firmly. We want credit for our catastrophe.

I am wheeled into the trauma room. Fifteen doctors and nurses and techs swarm the room. Someone sticks an IV in my arm, more rushed than the situation requires, and blood spurts everywhere. Blood is already everywhere, so no one notices.

“We all heard ‘sixty foot fall’ and had to see,” one PA tells me. The attention is intense but brief. They are expecting me to be clinging to life, but it is not so. Quickly, professionally, they arrive at a conclusion: stitches for the face, x-rays for the foot, and a tetanus shot for the road rash. No need for the IV.

STROKE ALERT sounds over the Emergency Room PA system, and they are done with me.

“You look a lot better than most climbers we get here,” the PA says, hours later, when she stitches my forehead together. “I had a friend who fell climbing in Eldorado Canyon a couple years ago. He died, actually.” She is unbelievably casual as she speaks and stitches. I feel nothing as her needle penetrates my skin. “You were very lucky.”

(If you want to see the big laceration before she stitched it up, click here. It’s fairly gory)

I cannot believe I am alive.

Simultaneously,

I cannot believe I fell.

I expect, at any moment, to awake with a jerk.

Years ago, my climbing mentor Meg and I attended a talk given by climber Quinn Brett, a woman who had suffered a similar-length fall while speed climbing on El Capitan. It was a well-publicized accident. Quinn was paralyzed.

At the time of the talk, Meg was coming off her own – recent and severe – climbing accident. I was young, only beginning to understand risk and consequence as a real physical presence in my life. We both hoped, I think, for some explanation.

Quinn gave a climbing slideshow; places she had been, expeditions and first ascents collected before her accident. The pictures were pretty, and she spoke candidly about her spinal injury. But we found no answers.

I did not even know what questions to ask.

The fall put an end to my Peru plans.

A summer in the Cordillera Blanca, the central idea on which I had organized my last year, gone.

Even as my partner drove me to the hospital, I knew everything was ruined.

I felt worse telling my climbing partners than my family.

Recovery has its ups and downs. Most days, I am fine. The forced hiatus from climbing has allowed me to let some other habits back into my life.

One summer evening I spend outside on a brewery patio, reading a book. It is warm, peaceful, and each mug of raspberry radler tastes better than the last. I have not earned the beers with a day climbing, but the novel is its own reward. I stay until the sun sets, the light fades, and the cold sets in.

With more effort than I’d like, I gather my crutch and hobble back to the car. I cannot put weight on my broken left foot. Once I can put weight, it will still be four more weeks walking in the boot. Then PT to restore a leg withered from lack of use. After that, I know, I’ll have to rehabilitate my mind.

“What happened to you?” a stranger asks. He has stopped walking away so he can watch me throw the crutch in the back of my minivan. I’ve removed the rear seats and installed a bed, for better sleeping at trailheads and climbing areas. Currently, the bed holds a knee scooter, arm crutches, and the bulky iWalk I have just thrown in. You could not have this injury with a sedan, I think.

“I fell,” I say to the man. “Rock climbing.”

“Ah climbing,” he says with an unrecognizable accent. “You like the adrenaline.” It is a statement he makes.

“No.”

The strength of my reply surprises us both.

I should explain to him what I mean. That to climb in control is to not chase adrenaline. That the moment before I lost my balance, I was in complete control; utterly relaxed. That when I landed on the ground, I had to take a picture to understand what injuries I had. That adrenaline was how I walked half a mile back to the car on a twice-broken foot. That this situation was utterly avoidable, completely unnecessary, and beyond unenjoyable. That the taste of adrenaline did not come close to making any of that worth it. That my summer is gone; and I am afraid, my passion might be too.

I should explain all of that.

But I won’t.

How could he understand?

Practical notes:

- This accident happened about six weeks ago. I am fighting the urge to not publish this, to keep revising until I have ‘fully integrated’ the experience. But perfect is the enemy of good, as they say, and the road ahead is long.

- I am mainly using the iWalk 3.0 crutch, which I highly recommend. The neat thing about this “peg leg” device is that it allows you to use your hands to carry things – very hard to do on traditional crutches or a knee scooter.

- I was wearing a helmet; an old-school Black Diamond Half Dome. I actually think the suspension of the helmet was responsible for the big cut on my forehead – I posted about that here, if you are interested.

- The route was The Green Spur, in Eldorado Canyon. I was linking pitches 1&2 from the ground to the eyebolt belay on the Red Ledge, and fell essentially the entire distance of the second pitch.

- The actionable takeaway: if you’re going to take the time to place gear, make sure it is reliable. I knew the cam I placed was bad, and had the opportunity to place more solid gear. I could have stacked the deck more in my favor.

- Reading: The Witcher series (Fantasy–quick reads and fun), Beyond the Mountain by Steve House (Ehh)

- Listening: Life is Good by Jesse Welles – any Jesse Welles, really.

- Watching: Andor (Disney+). Star Wars fan or no, this is must-watch TV; well-made and unfortunately relevant to our current politics.

- Speaking of politics: the current budget bill under discussion in the US Senate authorizes the sale of American public lands. Public land makes up much of the US West, including many prized climbing, backpacking and wilderness areas. The untouched wilderness is about the only thing still making America great, in my opinion. If you are a US citizen it is VITAL you write your representative and tell them your opinion on this issue. If we lose this land, we won’t get it back. Outdoor Alliance has built a really easy contact form: fill in your info, it will show you your representatives, and automatically contact them on your behalf. It’s quick and painless, and makes a real difference. Please fill it out if you care about this issue.

That’s all for now.

Oh, and: Always remember to thank your climbing partner, especially when they catch your fall and drive you to the hospital!!!!

So glad to hear you are recovering from your injuries. It sounds like you’re lucky you have injuries to heal from. The alternative unthinkable. Safe travels in the future.

‘We want credit for our catastrophe.’ Yep you got your sense of humor still there. Glad you made it through and I do hope, despie cancelled plans you are back out there again soon.

The confusion between ‘six’ and ‘sixty was good for a couple laughs. The lady doing intake was Asian and spoke English with quite the heavy accent. You gotta smile where you can in a situation like that.

Thank goodness it wasn’t worse. Wishing you a speedy recovery.

Thanks, Sheree!

That was one gory laceration. I admire your humor about it and your ability to relate the fall. Glad you had an able partner with you, too. Take care and keep climbing. Cheers

Yes I blanched at the picture when I saw it! Didn’t really hurt though.

Thanks for reading 🙂

Holy moly! Listen, you did it the hard way. I punctured my shin by walking into the pointy end of my dad’s stairlift and it’s taken 13 weeks of horrendous treatment to heal. At least you were doing something fabulous! Keep on truckin’. Safely!!! With a harness!!

Dang! That sounds super painful!! Wishing you all the best on your recovery too.

Harness indeed!