Shaqsha is an obscure mountain for Peru, despite the fact that it graces the cover of Brad Johnson’s “Classic Climbs of the Cordillera Blanca”, the most popular guidebook for the area.

Shaqsha was not on my radar at all until a chance meeting with Alejandro Urrutia and Rodrigo Ramos, a pair of Mexican alpinists. They were sitting in Cafe Andino, a western-style coffee shop in Huaraz popular with climbers, making a topo of a traverse of Chopicalqui they had just completed, from the SE ridge to the SW ridge.

They had been sick half their trip, they said, but had also managed to sneak in Shaqsha, via the left side of the ridge. A good climb, easy. “The right side also looked good,” they said, showing a photo of their tent pitched on the glacier in front of the face.

I wanted that picture. And off we went.

The Details

The Route: Shaqsa SE Face

The Grade: D+ (steep snow, 70-80deg, AI3-4)

The Summit: ~5,700m (sub-summit, Shaqsha Sur)

The Cordada

Diego and I had both been in Huaraz for a while, getting bored and feeling stale. I had come to Huaraz alone, although a few partners were supposed to join me. One came; one did not. My ticklist after a month was not as ambitious as I had hoped, although I had undoubtedly learned a lot about the people, the logistics, and the Blanca range.

I made a post in a Huaraz partner-finder group, and met Diego. From Argentina, he had driven 3.5 days non-stop from Buenos Aires with a group of friends, rotating shifts. His friends had departed, but still he stayed, hoping for a bit more.

We met in town a few times to feel each other out, and after talking with the Mexicans, eventually settled on Shaqsha as a get-to-know-you climb. His Patagonian climbing experience encouraged me, and we were able to get on fairly easily in either English or Spanish, depending on our mood.

The Approach

We agreed to hire a donkey to carry our packs. After a month climbing completely unsupported in the Blanca, I had no more pride about using support. We would pay for our climbing packs to be carried in, and hike with light daypacks.

The donkey and arriero cost us 100 soles ($27). Split two ways, $13.50 each. The donkey carried our 40kgs of gear 11 kilometers, over about 4 hours. We parted ways with the arriero, Juan, where the terrain became rocky, and sadly shouldered our heavy packs ourselves for travel across the moraine.

Here we made a mistake. As you travel up the rocky ground towards the obvious peak of Shaqsha, there is a large rock tower in front of you. We went left around this, but you should go right. This routefinding mistake ended up placing us on huge slabs below the glacier. These were crossable, but definitely not the ideal route.

Although we had planned to camp on the glacier, we tired ourselves out traversing the moraine. We ended up pitching our tent on the slabs below the glacier – a gorgeous spot I will refer to as “The World’s Worst Campsite.”

The Night

It had all the qualities you might want in a campsite: a big area, free of objective hazard from the mountain, a great view, running water nearby. All was good, except: it was inclinado – slanted.

All night, we found ourselves slowly creeping downhill. Turn on your side, and you immediately lost six inches. Sleeping at 5,000 meters is hard enough when you are flat and comfy. At the angle our campsite had, there was no chance of sleep.

Luckily we did not need to “sleep” long. The sun goes down around 6 p.m. in the Blanca, and we had planned to wake at 12 and start climbing at 1 a.m. The alarm was a welcome friend when it sounded. However, I stuck my head out the tent and saw the mountain shrouded in cloud. We went back to sleep, agreeing to check in an hour. Next time, we were in the cloud. Finally, by 3 a.m. the skies were clear and the mountain visible. It was a warm night, without frost. We put on our harnesses, donned our mountain boots, and struck out.

The Climb

Due to our choice of campsite, we first had to gain the glacier. Before going to bed, we had picked out a channel of snow which avoided the worst of the slab climbing.

Groggy, we walk 50 meters from our camp, don our crampons, and begin climbing. The gully offered easy mixed climbing on snow and rock. We warm up quickly, climbing with both 70m ropes stowed in our packs. Soon we reach the edge of the glacier, where we solo maybe 40-50 meters of low-angle AI2, interspersed with small crevasses. This is enough to get the lungs pumping, and I take advantage of the frequent horizontal platforms to stop and catch my breath.

Soon we reach the flat upper glacier, clean with very little in the way of crevasses. We quickly make our way across this flat plateau to the base of the mountain, as the moon rises behind the peak.

As we walk, the terrain continues to steepen, eventually reaching a point where it seems sensible to break out the ropes. We can not see it in the dark, but we can feel the presence of the bergshrund above us.

“Rimasha” Diego says, teaching me the Spanish word for the feature. “I cannot say it in English. Berk-Shrund. BURG-shrend. It is hard.”

“It’s hard for us too,” I say. “A German word, I think. We just borrow it.”

We rope up, attaching to our two 70-meter ropes. Diego takes the first lead, questing slowly up though the dark. It isn’t too steep, but still he places a snow picket occasionally for protection. We carry seven, unsure if we will need them for ascent or descent. Hanging from his harness to his heels, they clang around with every step. I can measure his progress up the mountain not only by the circle of light cast by his headlamp, but also from the sound.

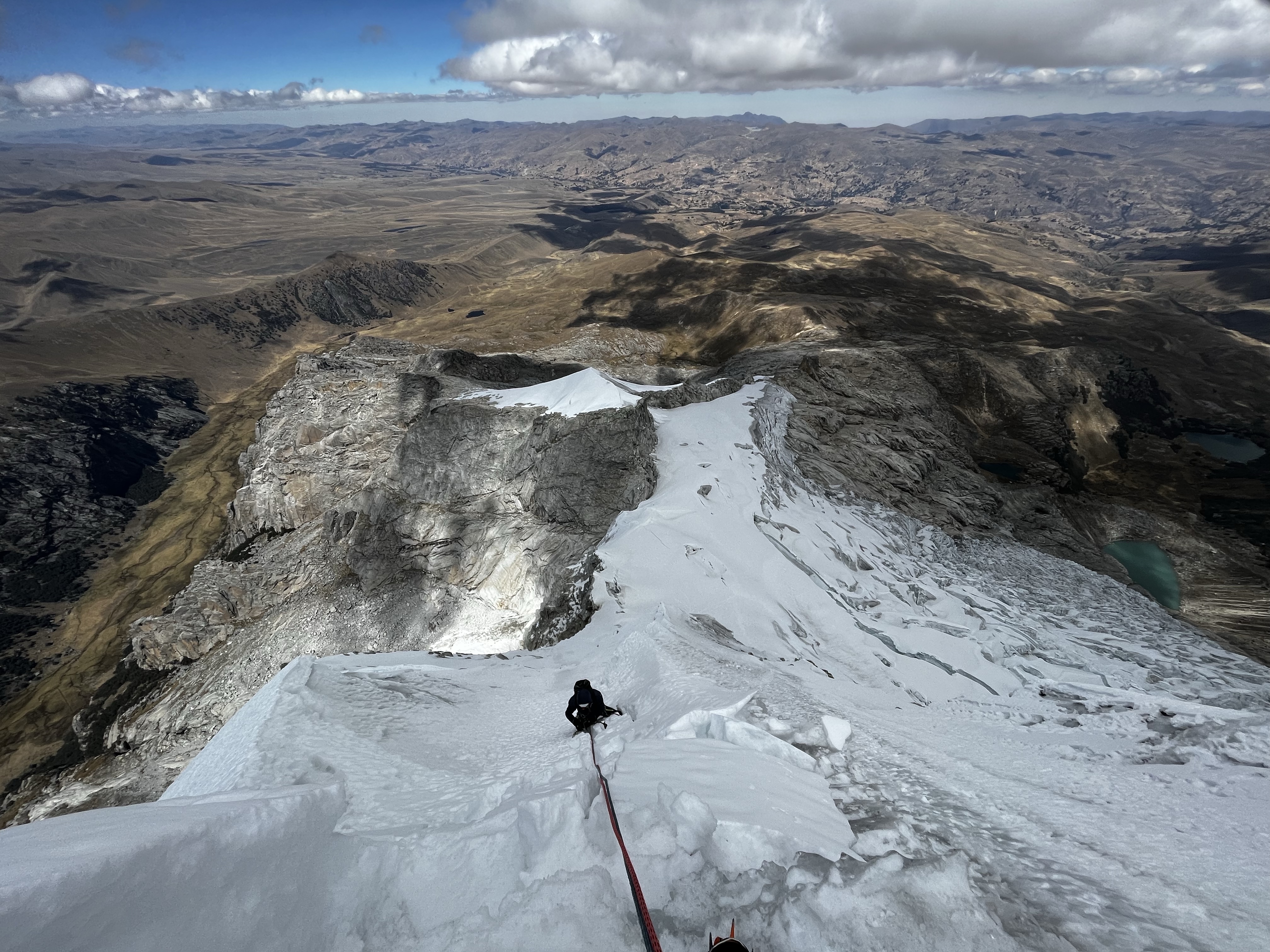

He leads a 100-meter pitch up and around the bergshrund, to the right. He sets a belay while I catch my breath on the simulclimb. The moment of crossing the gap is a little spooky, but I am reassured by his close presence, belaying me off of two pickets. We have gained the right side of the face. From here, our path is simple: up.

Our belay is situated below a small serac, so I quickly recollect the pickets, ice screws, and the two cams we have brought, and begin climbing. My line leads up and right from the belay, trying to climb quickly out of the area of danger. This takes longer than I would expect – I keep looking down, and seeing Diego still stationary, belaying. It takes ages for the 70 meters of rope to run out, at which point he begins simulclimbing.

The snow is soft, allowing for big supportive footholds to be kicked, but offering poor purchase for ice picks. I climb steepening snow, making steps in the slope with four or five kicks. I am stretching the distance between protection in order to climb a longer pitch. Our rack is sparse: with two pickets in the anchor below I have only five snow stakes, four ice screws, and the two cams. I climb roughly 140 meters, reaching a sheltered belay in a rock band which accepts the #1 cam on my harness, backed up with a so-so picket. The sun is starting to rise, and a few pieces of ice fall off the small cornice to our right, tumbling down the face.

I put Diego on belay and recover the ropes, and my climbing partner. We drink some tea from my thermos, and he starts out on the next pitch, a mixture of fragile snow, rock, and thin ice. Despite the bare rock, the face still holds enough snow and ice for us to progress. He climbs 35 meters, before spending all four ice screws and stopping in a sheltered stance below another rock band.

The next pitch starts with a treacherous traverse across rock slabs, intermittently covered with thin snow and ice. The ice quality unnerves me – it is aerated, and full of holes. It cannot be supported by much. I tip-toe across the section gently, mumbling curses in English and warnings to pay attention in Spanish.

After a few delicate meters, I reach the ridge, where there is visible blue ice. I sink an ice screw and relax. “That was probably the crux,” I say. “Take a picture!”

It was not the crux.

I continue up the face, staying left on the ridge. Here, I know there is ice, although at many points it is buried below a foot or more of soft snow, requiring serious excavation with my tools to access. I have climbed similar soft snow in Colorado, so I know I can attack this section. At least on this mountain there is ice below the snow, not often the case in my dry home state.

I slowly shovel my way up the face. It is difficult, tedious work, and kind of scary. With more ice screws I wouldn’t have been worried, but with one ice screw in the anchor, I only have three screws for the pitch. And knowing I need to maintain at least one screw for my own anchor, my protection options have suddenly become very limited. I laugh to myself, the only thing one can do in such an absurd predicament. I have only myself to blame for this situation, I think, as I inch upwards at 5,600 meters.

I continue to hug the ridge, where I am finding reliable ice. I am hoping to gain the crest and set a belay on the very spine of the mountain. The climbing is increasing in verticality. I try to calm my mind. I spot where I want to put the belay, only a few meters up, above a small vertical or near-vertical step.

I am very close now to the ridge crest, and the snow is beginning to change in character. Instead of a soft, sugar consistency, it is becoming harder. It accepts the pick of the ice axe without complaint. I can kick my crampons in, front-pointing in the snow, although it makes an unnerving sound. My internal radar sounds an alarm a little bit, but I am so happy not to be digging out every placement that I cheat for a few moves, using the firm snow with my left side while my right side still digs deep to find the bomber placements in the buried ice.

Suddenly — BOOM. The left side of the mountain collapses. A two-meter tall, triangular piece of consolidated snow falls away from me, down the left-side face. Luckily, Diego is tucked away on the other side of the crest, and is not at risk. Without realizing it, I had been climbing a wind slab, formed by transverse winds scouring across the face and depositing snow on the ridge.

With my heart in my throat, I carefully re-adjust my left tool and my left foot, finding ice. I take a few deep breaths, alone on the side of a huge mountain, and steel myself for the finish. There only remains one or two meters of climbing to reach a flat spot, a perfect belay unlocked by the collapse of the wind slab.

The climbing is steep – or feels steep, after what just happened. A fall probably wouldn’t kill me, I think, perhaps optimistically – but it would be disastrous. I have one ice screw left. I place it at eye level, enjoying the brief psychological respite it gives me. I move my tools once, move my feet to match, and realize I will need the screw for the anchor. Regretfully, I remove it. A deep breath, a few more sets of movement, and I reach the crest of the mountain. There is a perfect platform of ice to stand on, releasing the stress in my calves. I slam in the ice screw, clove hitch to it, and call off belay.

Ice and further snow slabs hang above me, and below I can see shattered bits of the wind slab I broke. It’s a scary belay, but it’s the best I am going to get. I place both my ice tools as good as I can, and tie them off with the screw, a mickey-mouse version of a three piece anchor.

Diego follows the pitch using the channels I have dug out. The climb continues to our left – fairly steep ice climbing. It looks doable, but I am sure Diego will want to bail, if he saw what just happened. Tucked away under a rock, it’s possible he didn’t.

We could v-thread off this ridge, I think. The ice is sufficient. Disappointing, perhaps, but acceptable. Let’s wait and see what he says, I think to myself. It appears that no more than one pitch remains before the summit.

A strong climbing partnership is formed when two people can support each other when the other is feeling weak. The moment Diego arrives at the anchor and says: “Yes, I’d like the next pitch,” our partnership became rock solid.

We replace the screw in the anchor with a V-thread, he takes all four screws, and using Quarks and glacier crampons he smashes the next lead — taking us right to the summit.

(Well, right below the summit, technically. But the summit proper looks incredibly dangerous, and we both have loved ones to return to. We have climbed the face, and feel no compulsion to go further).

We congratulate each other; take a few photos. “You look incredibly happy,” everyone will say, later, when I text them the summit photos.

The Descent

We rappel the left-side face on V-threads. This face is almost entirely ice, although it is covered with penitentes, annoying spikes of hard snow which constantly catch the rappel ropes. These features were nonexistent on the other side of the ridge. I am constantly cursing the penitentes as I lead the rappels — in Colorado the ropes would just slide down the mountain. But I am not in Colorado, I must remind myself. I am far from home, and not safe yet.

Five or six double-rope rappels on naked v-threads gets us down the face, although the ropes begin to stick as the day wears on. The last v-thread we sling with cord, and then add another thread for good measure, since the ice is becoming worryingly wet and weak under the hot equatorial sun. Below the bergshrund, Diego leads us down one final rappel off a picket we leave behind. “Better you do this one,” I say. “Estoy cagandolo todo.” It’s been nothing but a series of small errors during our descent, and I can’t help but feel I’m fucking it all up.

He laughs and graciously says nothing. I watch the picket flex and lift under his weight as he descends the less-than-vertical snow. Yummy. I hammer it back down, clip myself in for rappel, and try not to think of what I just saw. I have rappelled off plenty of pickets in the Blanca this summer, but never in such hot weather. Sweat drips down my brow as I rappel over a final crevasse to reach Diego.

We stumble back across the glacier to our slanted campsite.

When we left at 3 a.m. to start the climb, we’d both agreed: “We need to move the camp when we get back, if we aren’t completely destroyed.”

We are, of course, completely destroyed.

The Takeaway

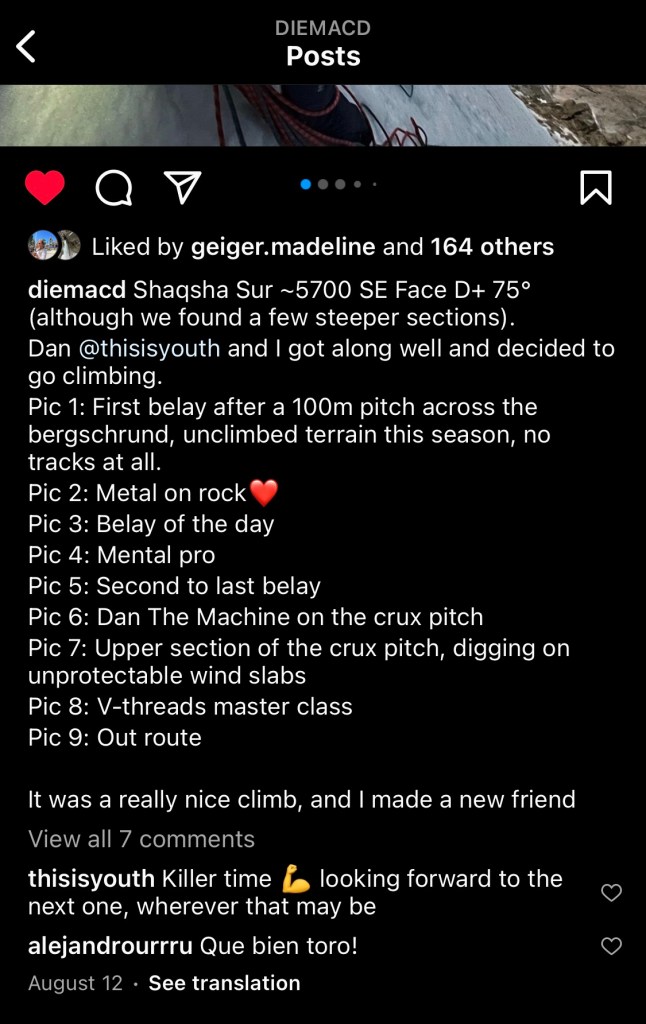

Here I have spilled 2,500 words to play-by-play this climb. Maybe the details will be useful to someone, some future season. But this post doesn’t sum up the emotional experience of the climb. Diego, in his second language, nails it in only a dozen words:

“It was a really nice climb, and I made a new friend.”

A few weeks later, the Hermanos Pou (professional Basque climbers) would follow in our footsteps, repeating the route with a camera crew and a drone. Check out their footage:

This would be my last mountain in Peru. A satisfactory end to the season. But I’ll be back.

Any photos with a date are Diego’s, others are mine. More photos here: https://medium.com/p/1157ad047bb7

PS: if you climb this mountain after reading this trip report, leave a comment with recent conditions!! I see you guys all googling in from Peru.

PD. Si escalas a esta montanita despues de leer, postea un commentator con conditioned actualizadas! porfa! Ingles o Castellano o Frances no importa, la fraternidad montanero te agradecerá. Aguevooo.